*The below article and information are based on lab research data of Adipotide, this is not medical advice in any kind of shape or form.

Most weight loss peptides are designed to change the behavior of fat cells — make them release energy or stop them from storing it — or kill appetite. Adipotide is interesting because it leaves those models behind.

This investigational peptidomimetic doesn’t try to manage fat cells. It brings about their demise.

Brutal? You bet. You don’t usually think about it, but white adipose tissue needs to be fed, too. It can’t stay alive without the large, dense network of blood vessels that supplies them. The researchers who developed Adipotide decided to take advantage of that vulnerability.

Is it effective? Also yes. Adipotide starves fat tissue — so people who would really benefit from losing weight don’t have to starve themselves to get to their goal.

Interesting? Endlessly so, and that explains why research into this new peptide (the most prominent study was only published in 2011, so Adipotide is practically a baby) is really picking up steam now.

A Brief & Interesting History of Adipotide

The team that developed Adipotide — led by Dr Wadih Arap and Dr Renata Pasqualini — were actually trying to develop a compound that could starve cancerous tumors. They started with a massive library of viruses engineered to show short peptide chains on their surfaces. These, they injected into mice with tumors — so they could see which ones bound to their blood vessels.

That work is fascinating (and still a promising line of inquiry), but fat and tumors have a lot in common. Both die without blood supply. It didn’t take them long to realize that the same basic idea could be developed into an obesity treatment.

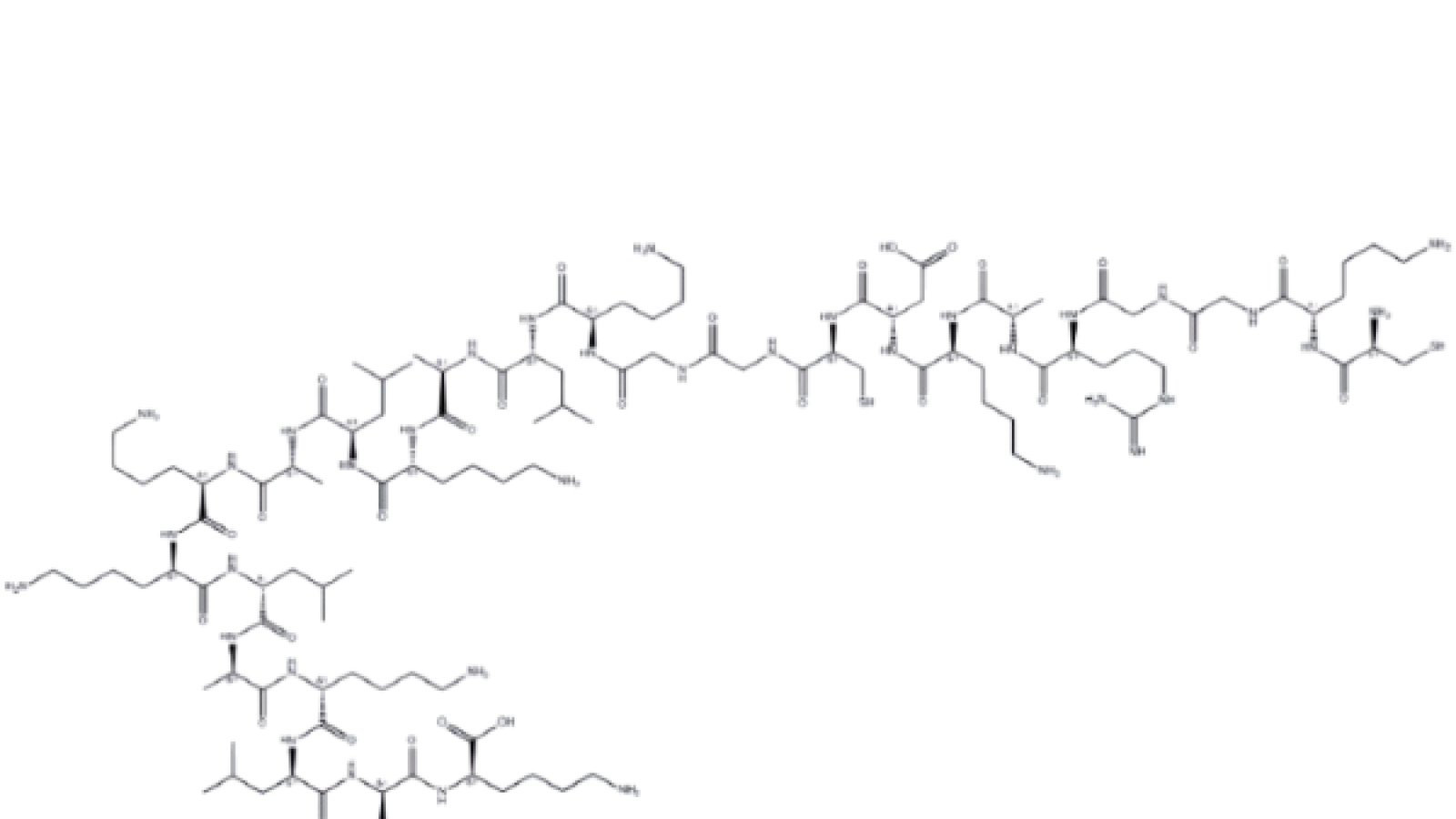

They did. The researchers made a peptide sequence (CKGGRAKDC, if you’re curious) that sticks only to two proteins in the blood vessels that supply white fat tissue — Prohibitin and Annexin A2. It would now take just one more component to make the peptide work. A cell-killing sequence. KLAKLAK.

They work beautifully as a team — the first portion delivers the second to the places where it can kill off fat by ordering white adipose tissue to set a self-destruct chain in motion. Without oxygen, without nutrients, that fat dies. Other processes take over to clear it out.

The most famous study, published in Science Translational Medicine, was a great success. Obese monkeys lost 11 percent of their starting body weight. In less than a month. Adipotide is a whole new way to destroy fat (in the most literal sense). Its potential has been proven — and its development opens the door for all sorts of new peptides with similar homing capabilities, too.

Adipotide Research Proved It Can Starve Fat Cells — And What Other Applications Did Scientists Discover?

If you know your peptides, you also know that many are multitaskers that influence biological processes pretty much all over the body — sometimes with such diverse research applications that it would make your head spin. Adipotide isn’t like that. It’s a single-purpose peptide. That’s not a shortcoming. It was made that way. Researchers designed it to do one thing (kill white adipose tissue) and that one thing is all it does.

Don’t let that single-purpose mechanism trick you into thinking all Adipotide research comes to the same conclusion — or that, if you’ve ready one study, you already know what every other paper will say, too. That’s not quite true.

Early Work and Proof of Concept — Adipotide in Rodent Studies

The first in vivo studies, done in rodents, had results that were nothing short of revolutionary. Obese mice treated with Adipotide successfully lost weight — and describing the results as “not too shabby” would be an understatement. Within just four weeks, they managed to shed a grand total of 30 percent of their starting body weight. [1]

Mice and rats have genetic codes similar enough to those of people to make them worthwhile research targets, but they’re not so similar that everything that works for them also works for humans. This early research didn’t prove that Adipotide would also make people lose weight, because rodents respond quite differently to some peptides.

These studies did confirm one important thing. Adipotide worked as intended. The peptide selectively targets Prohibitin on the blood vessels that supply white fat. It induces programmed cell death and orders fat to go meet its maker — and Adipotide does this without damaging other vascular networks. [2]

Adipotide Also Worked on Rhesus Monkeys

With that finding in the bag, researchers wanted to probe if Adipotide could achieve similarly impressive results when it was given to primates. They chose rhesus monkeys because they’re physiologically very similar to humans — treatments that work for them usually do for people as well. [3, 4]

We already teased the findings. Naturally obese rhesus monkeys lost 11 percent of their starting body weight on Adipotide. That result didn’t take long, either. It happened in just four weeks.

Three things really matter here. First, weight loss usually takes a lot longer than that. If you look at some of the GLP-1 peptides now studied for weight loss, you’ll see they’re very effective — often more so than Adipotide. You’ll also see they depend on a dose of patience. Weight loss results take longer to become apparent.

Second, the rhesus monkey study proved that Adipotide exclusively zaps white adipose tissue. Muscles also contain fat (“intramuscular fat”), and people who lose weight through dieting sometimes pay the price in lost muscle. That doesn’t happen with Adipotide. This peptide gives a clean, targeted way to facilitate weight loss. One that preserves hard-earned muscle.

Third, the monkeys were selected because they had “clinically abundant abdominal fat.” That kind of fat is especially dangerous, because it comes with a massive risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorder, and type 2 diabetes. By the end of the study, the subjects had normal, healthy waist circumferences — raising hopes that Adipotide can be used to reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

The research continued with other kinds of monkeys — and every study showed that Adipotide successfully starves fat.

Adipotide and the Potential to Improve Metabolic Markers and Slash the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes

Obesity doesn’t get called a global epidemic for nothing. It worsens health outcomes across biological systems, starting with the risk of stroke and heart attack and going all the way to osteoarthritis. Type 2 diabetes is, however, one of the biggest risks.

It’s no surprise that researchers were keen to see if Adipotide had any effects on insulin resistance, then. The glucose tolerance tests they did at every stage of the study showed that it did. It took less insulin for the insulin-resistant subjects to respond to the glucose test after Adipotide than it did before.

The most exciting part? The literature now shows that eliminating visceral fat, the cause of metabolic inflammation, makes a metabolic reset that tackles one of the main causes of type 2 diabetes possible.

Full Circle: Adipotide in Cancer Research

Remember? The researchers who developed Adipotide didn’t start with weight loss. At first, they’d wanted to create a peptide that would starve tumors of their blood supply. It was only after they realized the weight loss potential that they changed gears and started research obesity treatment compounds.

That origin story is hard to escape, and other researchers would inevitably pick this thread up again. Preclinical research with prostate cancer models has demonstrated that Adipotide can slow the growth of some cancer cells, so the peptide might have a part to play in the field of oncology. [5]

More exciting (because of its broader applications) is, however, the general mechanism. Adipotide proved that vascular targeting is possible — peptides can be engineered to selectively starve only certain types of blood vessels, while leaving others completely untouched.

That data is valuable. It makes research into new cancer-zapping peptides possible. New obesity treatments are important on their own, but it sure would be interesting if Adipotide could come full circle, and inspire new blood vessel killers that starve tumors. [6]

How Have Adipotide Studies Administered the Peptide?

Adipotide has one main job — it was created to get into the blood stream, hunt around for the vasculature that keeps white fat fed, and deliver its “warhead.” Researchers carefully picked the delivery route used in most Adipotide studies to make this possible.

Some people will be surprised to hear that most research (among which the rodent and primate studies we cited earlier) relies on intraperitoneal injection. IP injection gets the peptide straight into the area around the abdominal organs.

This works for a couple of different reason. First, the peritoneum is large and packed with blood vessels. Injecting Adipotide there gives the peptide the best odds of reaching its target. Then, there’s the fact that IP injections are easy and quick to administer — very important for large-scale rodent studies.

Some researchers have, however, experimented with subcutaneous and intramuscular delivery as well. The rate at which at which Adipotide gets absorbed is slightly slower there, subQ injections still have a predictable systemic effect. Most researchers think of them as more applicable to human clinical trials.

What is The Researched Dosing Protocols for Adipotide In-Vitro & Other Models?

Finding the best dosing protocol is always a balancing act. Researchers try to find the dose that’s most effective — while at the same time keeping side effects to a minimum.

The trial that helped obese rhesus monkeys lose 11 percent of their body weight within a 28 days used a daily dose of 0.5 mg per kilogram. This same dosing protocol inspired further primate research. Some studies use higher or lower doses, however. If you intend on reviewing the literature, you’ll come across doses from 0.5 mg all the way to 3 mg per kg of body weight.

Total study length also matters. Daily dosing is standard in Adipotide studies, but the compound is also known to put some stress on the kidneys. Because Adipotide induces weight loss very quickly, study durations of around four weeks are very common. Once that period ends, subjects are given a break of four to eight weeks before potentially starting on a new round.

The most common longevity and “bro-science” dosing protocols in Reddit talk about:

- ~0.5mg per day for the first week.

- Next week, increasing it to 1mg per day and keeping it that way for ~3-4 weeks (minor increases are also welcome every week depending on study subjects’ needs).

- *keep in mind that this is anecdotal, reddit stories, not medical advice or encouragement.

Researchers follow how the model responds to the compound very carefully by doing blood work — not only before and after the study, but also at set intervals within it.

FAQs

Good question. Once you know that Adipotide finds the blood vessels that keep fat alive and destroy them, it’s only logical to wonder what happens after. White fat starved of nurtients enters a state of programmed cell death — at which point the immune system sees it as trash and starts cleaning it up.

Where peptides that slash appetite and food cravings put a stop to excessive eating, Adipotide goes to war with existing fat. That’s a different weight loss mechanism, and it could be more effective in cases where subjects have localized excessive fat stores and where changing dietary habits isn’t possible. Even more importantly, zapping existing fat also has the potential to make all the difference in cases where obesity is the source of an acute metabolic emergency. Adipotide could serve as a first responder — because it works fast.

The observed effect Adipotide has on the kidneys has been the biggest reason to limit doses in studies. Research has found dehydration to be a persistent side effect. These effects reverse after the study finishes, and they’re one reason Adipotide studies are usually shorter.

Absolutely. Adipotide proved vascular targeting as a viable strategy, and researchers are actively working on finding new “molecular zip codes” to target the receptors on different kinds of blood vessels. Besides tumors, they include arthritic joints. [7]

It’s neither worse or better. It works differently. GLP-1s target your appetite, insulin signaling and gut hormones.

And Adipotide specifically targets fat cells. It is very effective. But it’s less studied compared to GLP-1s, GIP, and GCG. And it’s shown to put additional strain on kidneys. So people with kidney issues should probably consider GLP-1s better.

Scientific References and Sources

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3666164/[↩]

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15133506/[↩]

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20103704/[↩]

- https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/scitranslmed.3002621[↩]

- https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.29344[↩]

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0196978117303030[↩]

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128225462250016[↩]

Cart is empty

Cart is empty